Kara Walker: American painter

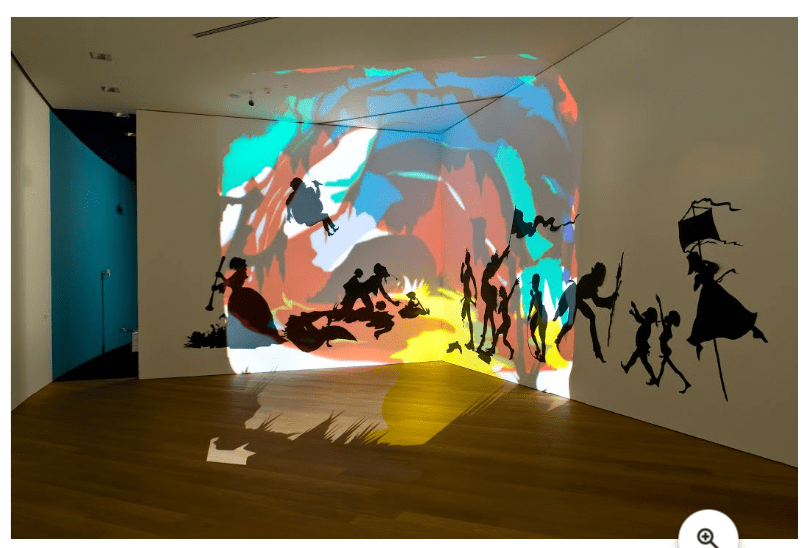

Walker attended the Atlanta College of Art with an interest in painting and printmaking, and in response to pressure and expectation from her instructors (a double standard often leveled at minority art students), Walker focused on race-specific issues. She then attended graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design, where her work expanded to include sexual as well as racial themes based on portrayals of African Americans in art, literature, and historical narratives. Walker, an expert researcher, began to draw on a diverse array of sources from the portrait to the pornographic novel that have continued to shape her work. Other artists who addressed racial stereotypes were also important role models for the emerging artist. While still in graduate school, Walker alighted on an old form that would become the basis for her strongest early work. Widespread in Victorian middle-class portraiture and illustration, cut paper silhouettes possessed a streamlined elegance that, as Walker put it, “simplified the frenzy I was working myself into.” Kara Walker is among the most complex and prolific American artists of her generation. She has gained national and international recognition for her cut-paper silhouettes depicting historical narratives haunted by sexuality, violence, and subjugation. Walker has also used drawing, painting, text, shadow puppetry, film, and sculpture to expose the ongoing psychological injury caused by the tragic legacy of slavery. Her work leads viewers to a critical understanding of the past while also proposing an examination of contemporary racial and gender stereotypes.

Walker’s first installation bore the epic title Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994), and was a critical success that led to representation with a major gallery, Wooster Gardens (now Sikkema Jenkins & Co.). A series of subsequent solo exhibitions solidified her success, and in 1998 she received the MacArthur Foundation Achievement Award. Despite a steady stream of success and accolades, Walker faced considerable opposition to her use of the racial stereotype. Among the most outspoken critics of Walker’s work was Betye Saar, the artist famous for arming Aunt Jemima with a rifle in The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), one of the most effective, iconic uses of racial stereotype in 20th-century art. Nonetheless, Saar insisted Walker had gone too far, and spearheaded a campaign questioning Walker’s employment of racist images in an open letter to the art world asking: “Are African Americans being betrayed under the guise of art?” Walker’s series of watercolors entitled Negress Notes (Brown Follies, 1996-97) was sharply criticized in a slew of negative reviews objecting to the brutal and sexually graphic content of her images. Saar and other critics expressed concern that the work did little more than perpetuate negative stereotypes, setting the clock back on representations of race in America. Others defended her, applauding Walker’s willingness to expose the ridiculousness of these stereotypes, “turning them upside down, spread-eagle and inside out” as political activist and conceptual artist Barbara Kruger put it.

Fierce initial resistance to Walker’s work stimulated greater awareness of the artist, and pushed conversations about racism in visual culture forward. In 1998 (the same year that Walker was the youngest recipient ever of the Macarthur “genius” award) a two-day symposium was held at Harvard, addressing racist stereotypes in art and visual culture, and featuring Walker (absent) as a negative example. Rising above the storm of criticism, Walker always insisted that her job was to jolt viewers out of their comfort zone, and even make them angry, once remarking “I make art for anyone who’s forgot what it feels like to put up a fight.”

In 2007, TIME magazine featured Walker on its list of the 100 most influential Americans.

In 2008 when the artist was still in her thirties, The Whitney held a retrospective of Walker’s work. Though Walker herself is still in mid-career, her illustrious example has emboldened a generation of slightly younger artists – Wangechi Mutu, Kehinde Wiley, Hank Willis-Thomas, and Clifford Owens are among the most successful – to investigate the persistence and complexity of racial stereotyping.

(YouTube link below; skip to 4:25)

All the love,

Cheyenne

Great article. It’s very unfortunate that over the last 10 years, the travel industry has had to take on terrorism, SARS, tsunamis, bird flu virus, swine flu, as well as the first ever entire global recession. Through all this the industry has proven to be robust, resilient in addition to dynamic, finding new approaches to deal with trouble. There are constantly fresh issues and the opportunity to which the field must once again adapt and behave.

LikeLike

Your style is unique compared to other people I’ve read stuff from. Thanks for posting when you’ve got the opportunity, Guess I will just book mark this web site.

LikeLike

Thank you. I’d like to think the my style is unique and different than someone else’s . Thank you for reading my content and liking what you read.

LikeLike

Hi! This post could not be written any better! Reading this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept chatting about this. I will forward this write-up to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike